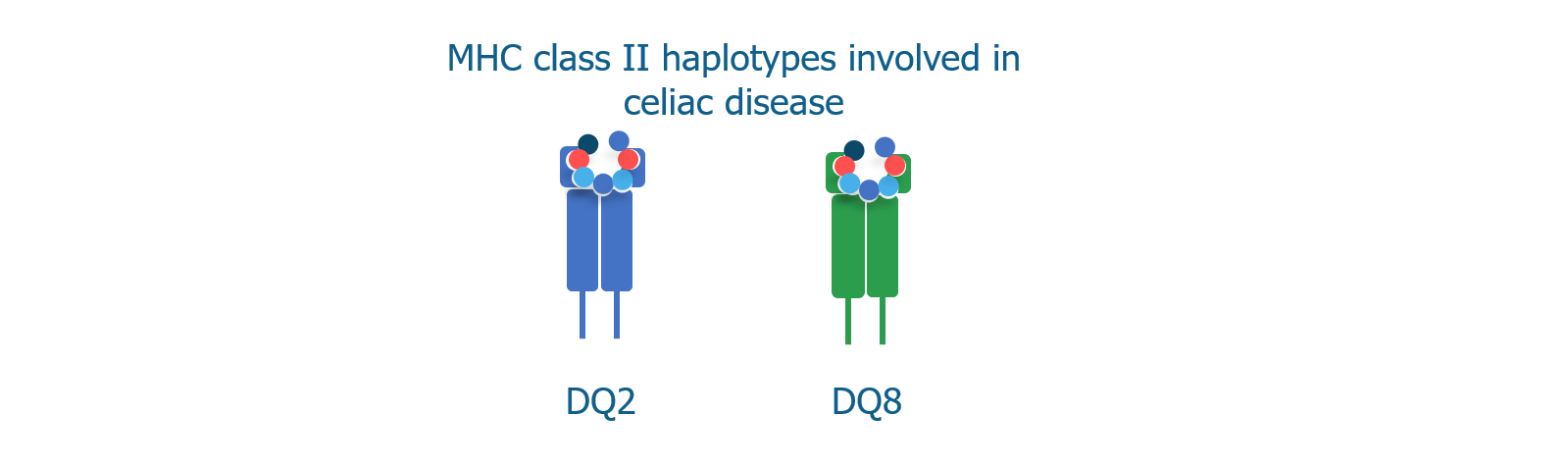

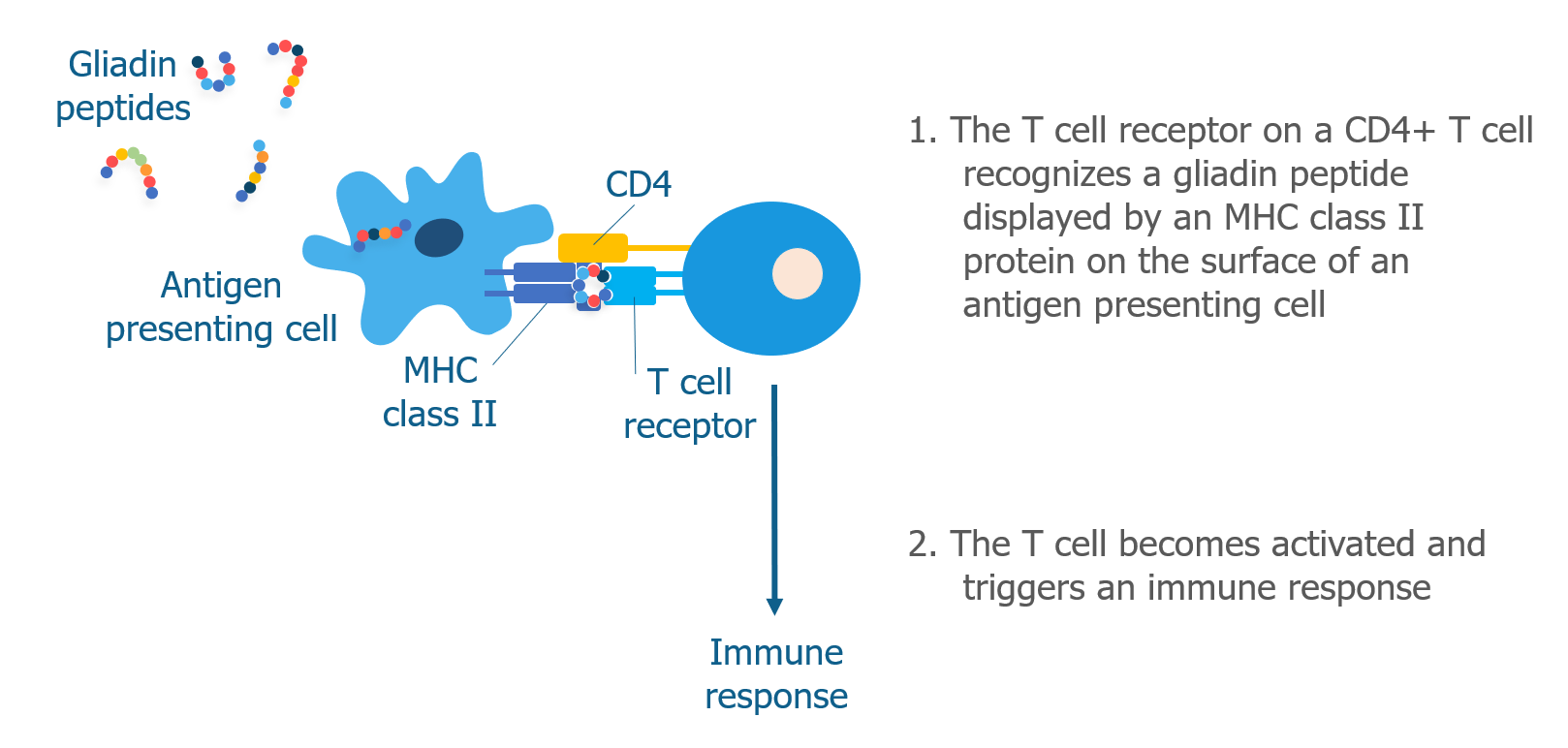

We’ve talked a lot about T cells and MHC proteins and how they recognize gluten. But B cells also play a key role in celiac disease.

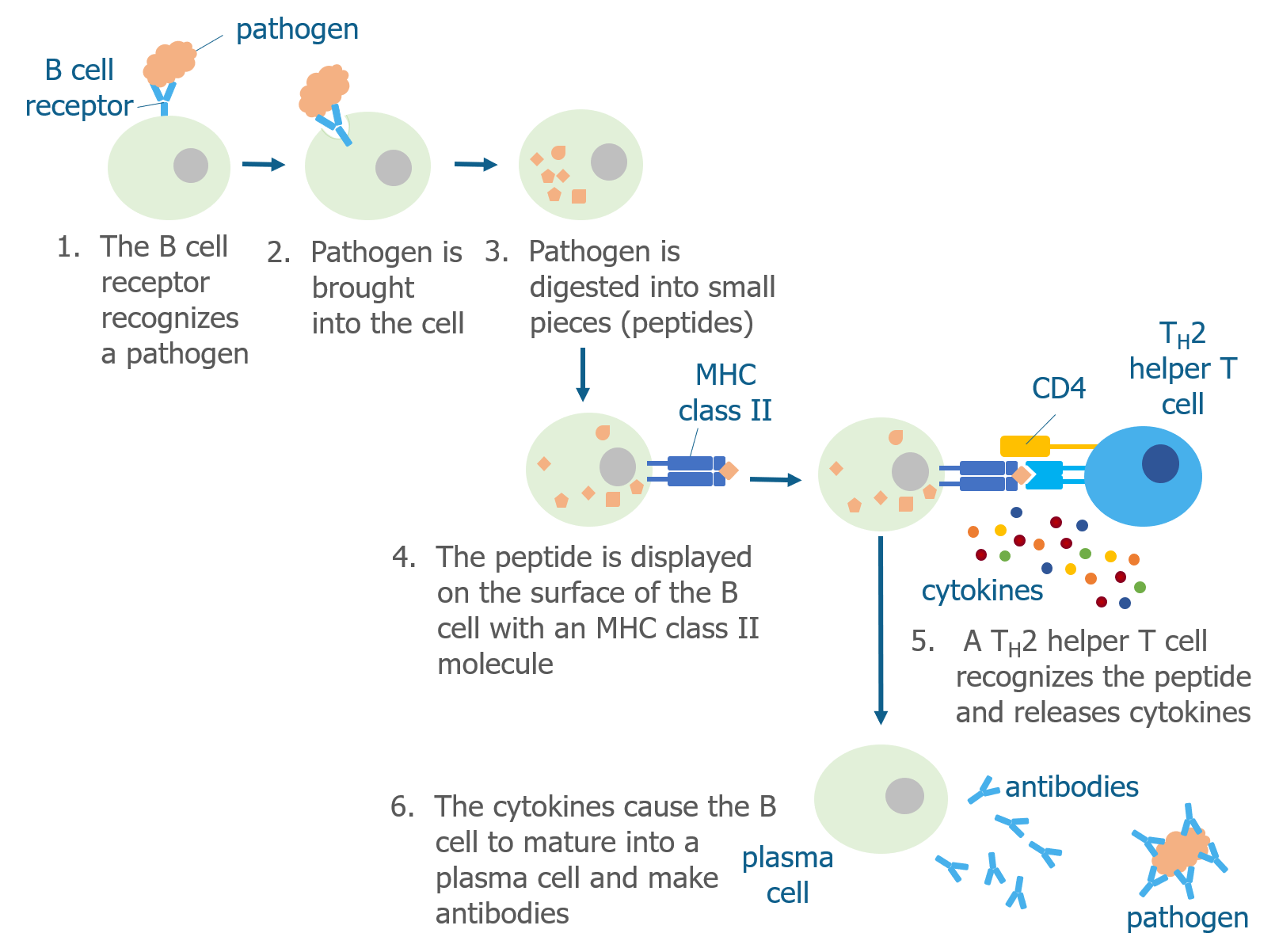

Like T cells, B cells have receptors (B cell receptor or BCR) on their surfaces that recognize specific pathogens. Unlike T cells, they do not need antigen presenting cells to display a pathogen peptide for them—they are able to recognize pathogens on their own. Each B cell has a unique type of B cell receptor that is capable of recognizing only a few antigens.

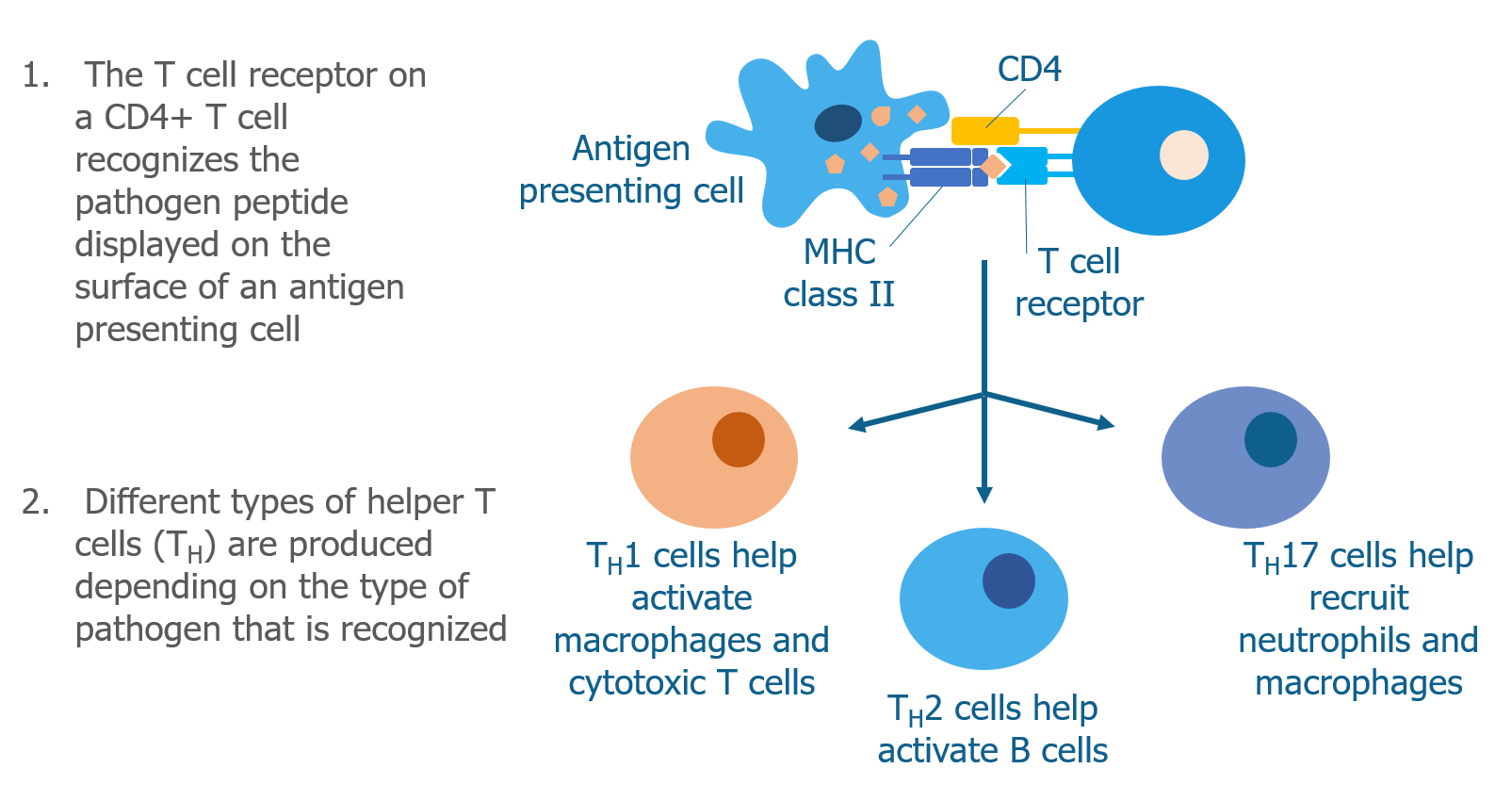

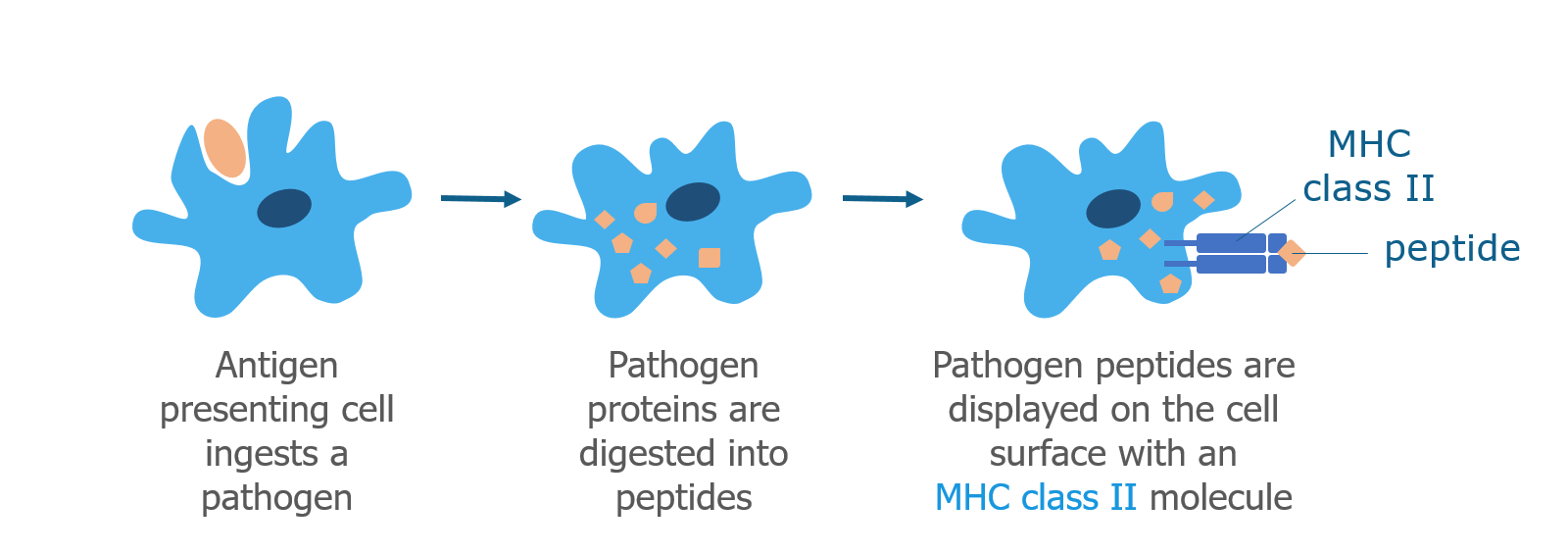

When a B cell bumps into a pathogen that it recognizes, it brings the whole pathogen into the cell and digests it into peptides. As discussed above, B cells are antigen presenting cells and display pathogen peptides on their surface in complex with an MHC class II molecule. They do this because they need the help of Th2 helper T cells to become activated. Th2 helper T cells that have already recognized the same pathogen (by interacting with other antigen presenting cells) are able to recognize the antigen displayed by the B cell. When this happens, Th2 cells produce cytokines that cause the B cell to mature into a plasma cell.

The main role of plasma cells is to produce proteins called antibodies (also known as immunoglobulins), which are Y-shaped proteins that recognize the same pathogen that the B cell originally recognized. Plasma cells release these specific antibodies into the surrounding tissue where they find and stick to the pathogen.

By doing this, antibodies stop the pathogen from spreading and mark it for destruction by other immune cells. This type of immune response is often called the antibody-mediated immune response.

There are five main classes of antibodies—IgA, IgD, IgE, IgG, and IgM—each of which have different roles. Two of these classes, IgA and IgG, can be found at high levels in blood samples.

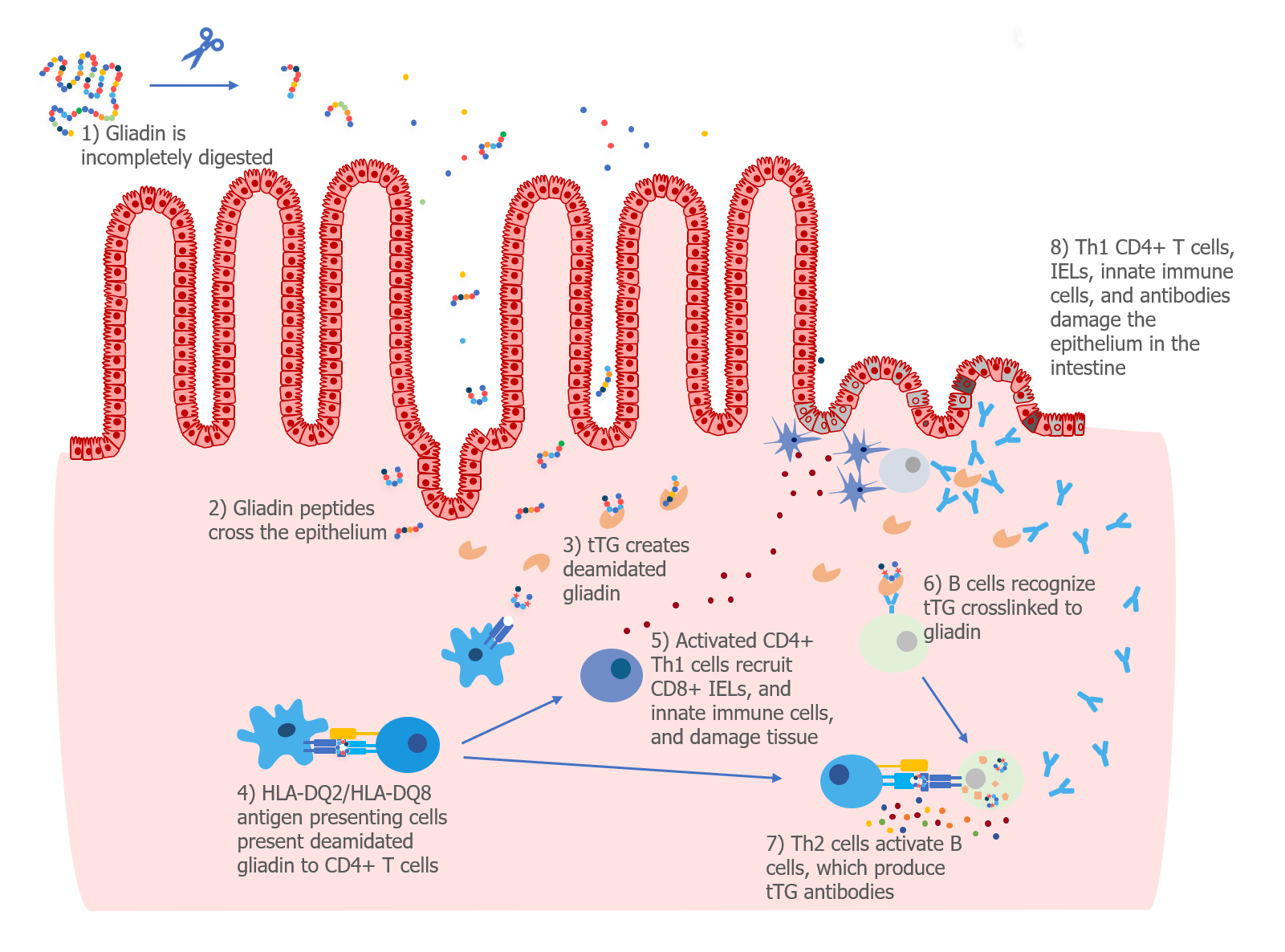

How Are B Cells Involved in Celiac Disease?

In the 1980s, researchers discovered that patients with celiac disease had high levels of antibodies that recognized gliadin (a protein in gluten) in their small intestine.1 Patients with celiac disease were also found to have auto-reactive antibodies—that is, antibodies that recognize normal “self” proteins.

Researchers developed a blood test that was able to detect IgA antibodies that recognized a type of tissue called endomysium.2 In 1997, Dr. Detlef Schuppan and his team discovered that IgA antibodies in the blood of patients with celiac disease recognized a specific protein in the endomysium—a protein called tissue transglutaminase (tTG).3 The antibodies to gliadin, endomysium, and tTG disappear when patients adopt a gluten-free diet, which suggests that these antibodies are made as part of an immune response to gluten.

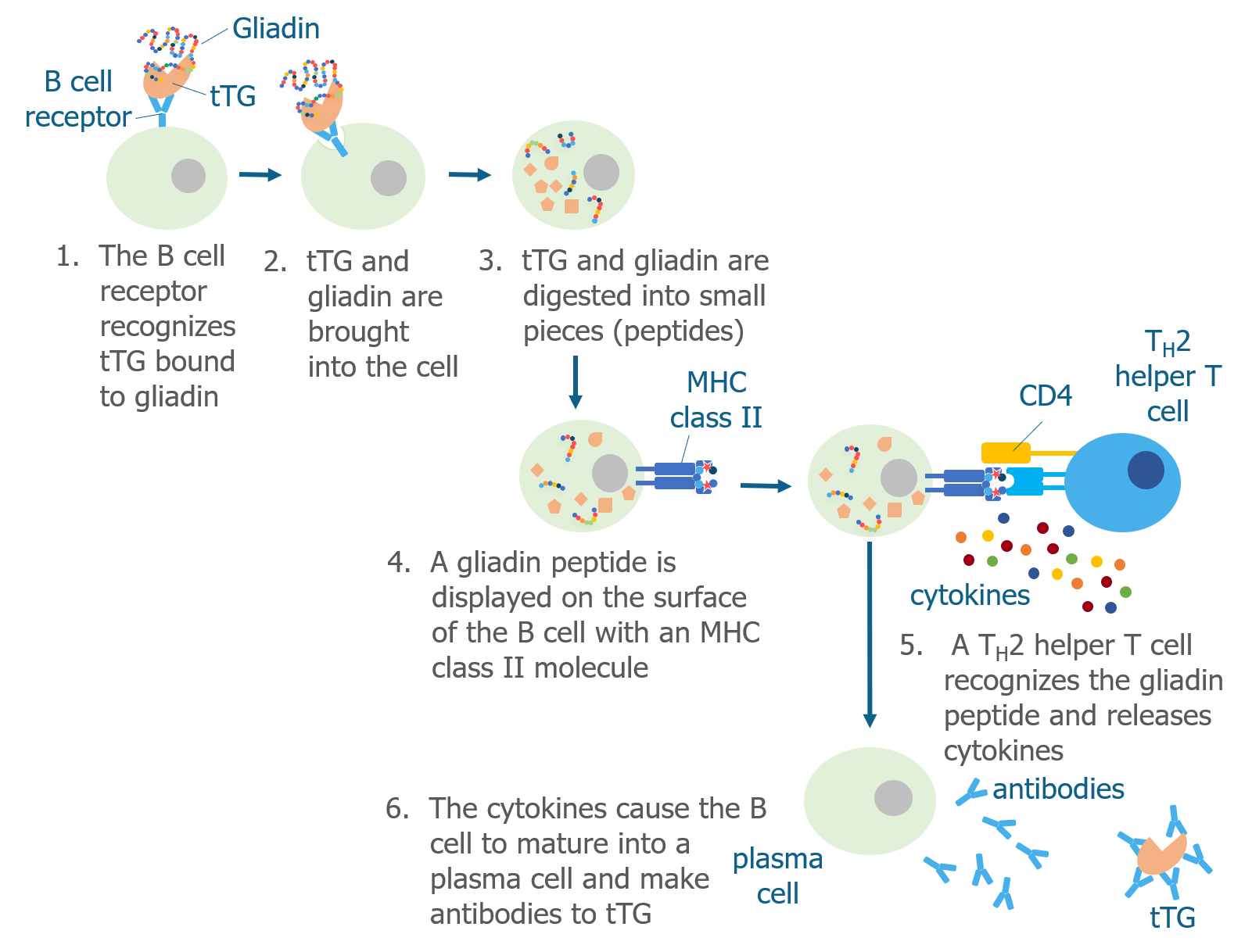

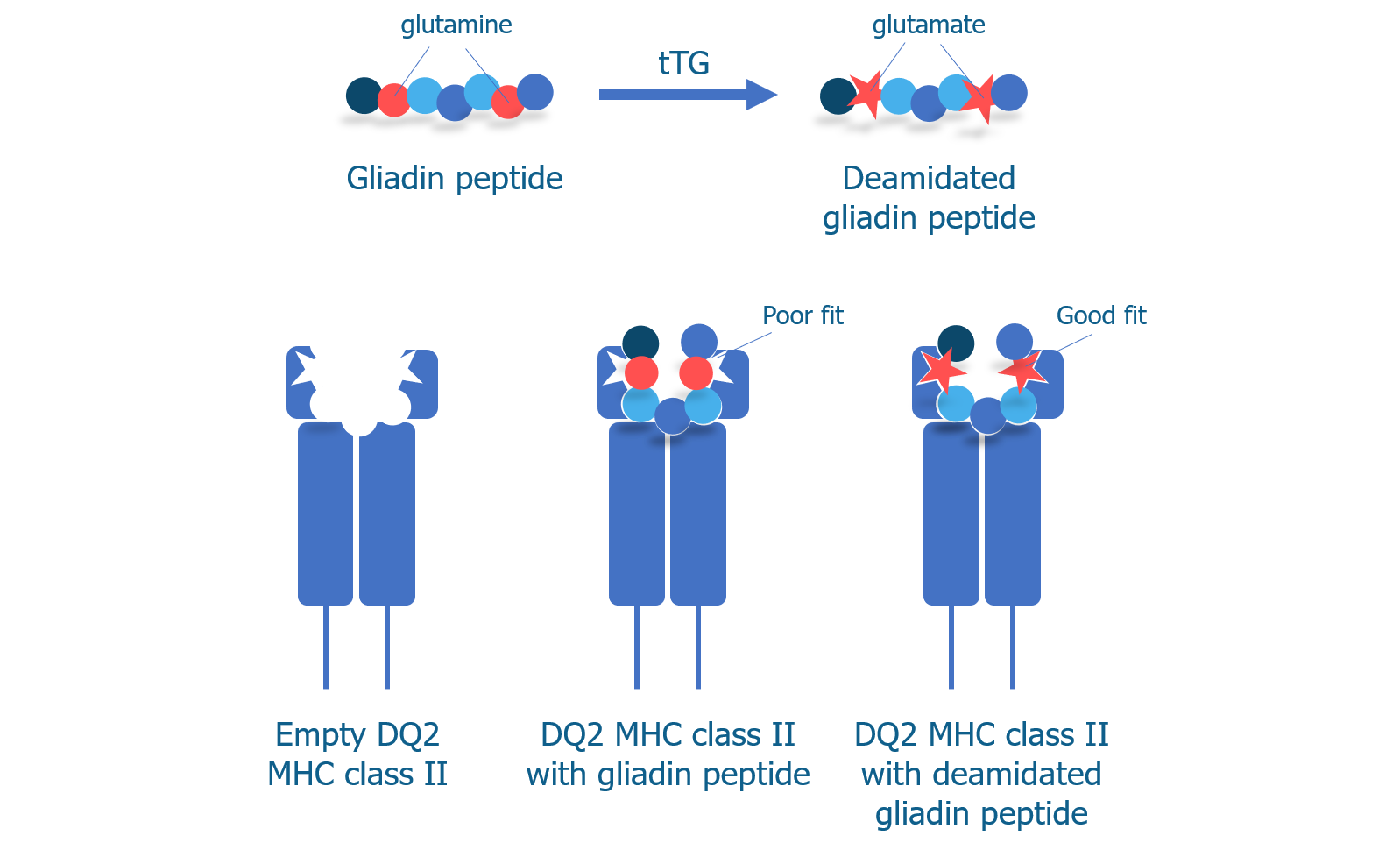

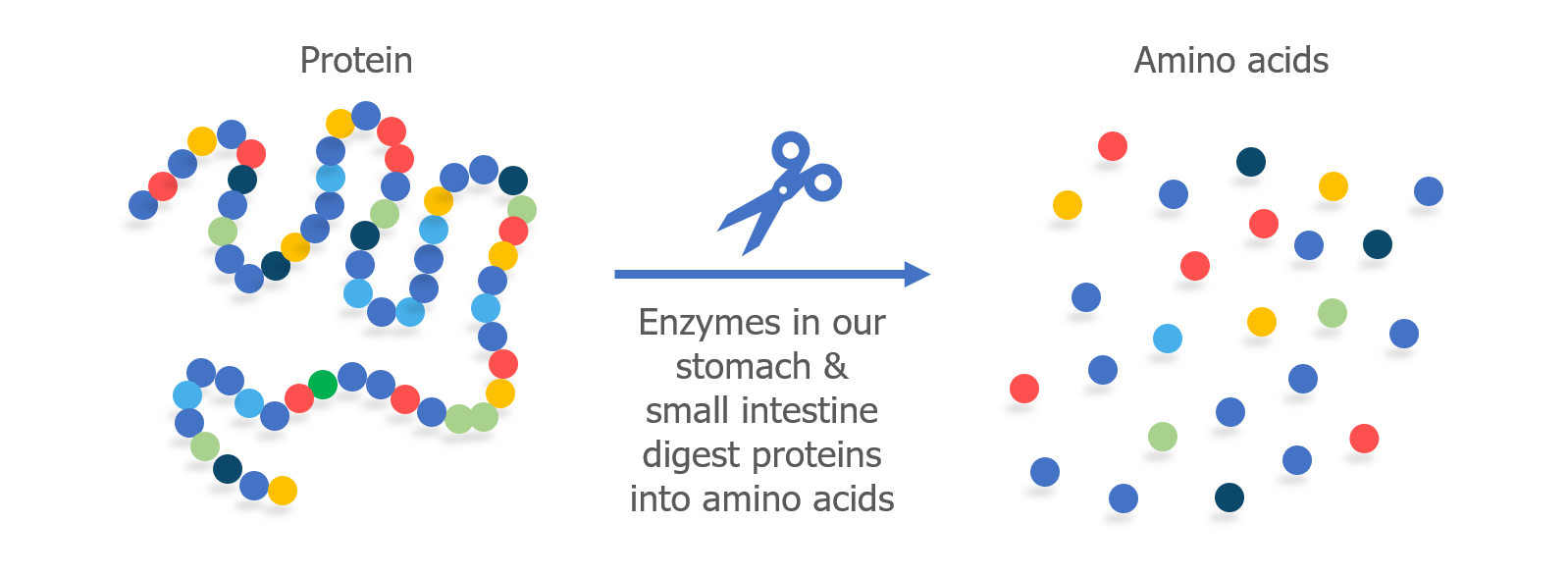

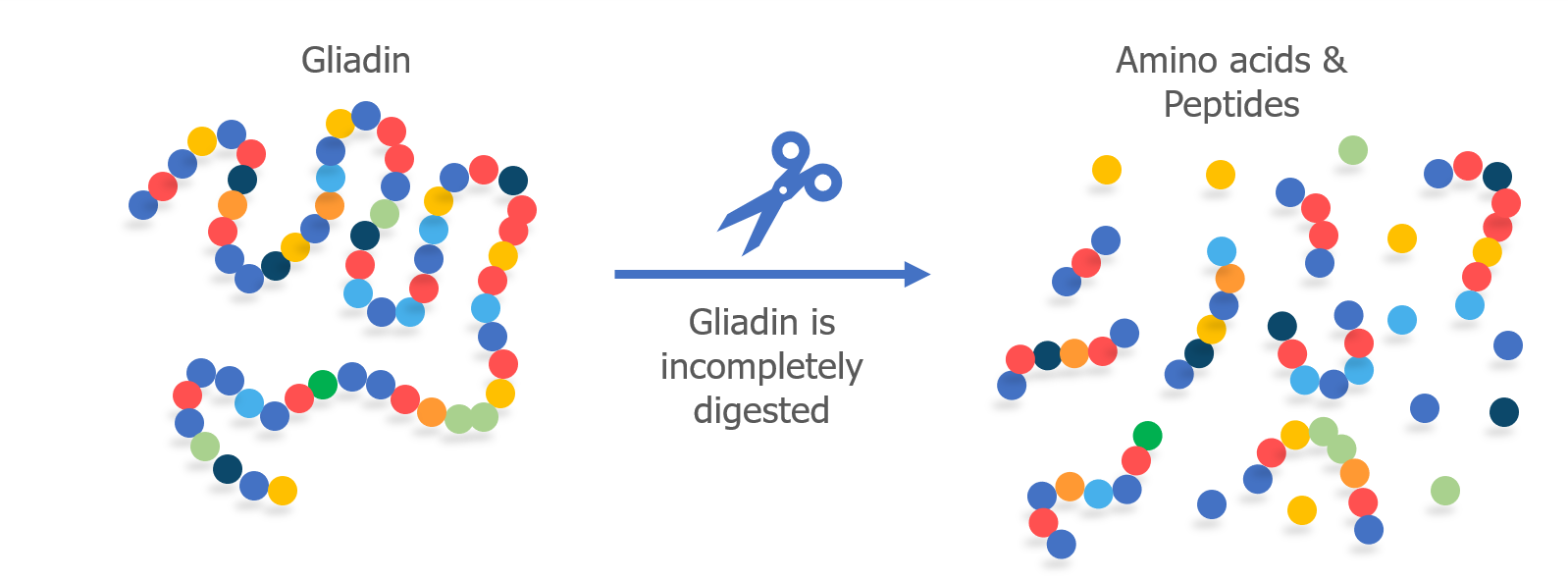

We know that T cells can recognize deamidated gliadin peptides and begin an immune response, so it makes sense that B cells might produce antibodies to gliadin if they mistakenly recognize it as a pathogen. But why would B cells produce antibodies to tTG, a normal protein in the body?

As we discussed above, tTG is the enzyme that is responsible for converting the glutamine amino acids into glutamate amino acids to produce deamidated gliadin peptides, which have increased immunogenicity. In addition to changing glutamines to glutamates, tTG can also cross-link the gluten peptide to itself.

Researchers are still trying to understand exactly how gluten causes B cells to make antibodies that recognize tTG, but they think that B cells ingest tTG that is cross-linked to a gliadin peptide. Then, Th2 helper T cells that recognize gliadin help B cells produce antibodies to tTG.